Environmental impacts of wind farm development

When beginning the development of a wind farm, it’s not just the physical design of a property you should consider, but the environmental factors as well.

Consider the eagles before development

As environmental scientists, our role is to inform our clients about the risks to natural resources and wildlife; in particular, avian life. Using information about the natural environment, we can provide recommendations to our clients for ideal locations to construct potential wind turbines. Wind energy infrastructure can pose a great risk to birds and eagles and our research helps protect them from turbine injuries and/or fatalities. If an eagle is killed or injured by a windmill, the wind farm owner may be in violation of a federal law and face a penalty.

Wind farm eagle surveys

WSB has recently been collecting data about the presence of golden and bald eagles at a wind farm project in Montana. In recent surveys, golden eagles have been observed at the 6,000-acre site and are potentially at-risk from the wind farm development. Golden and bald eagles are protected by the Bald and Golden Eagle Act created in 1940 (and expanded to include goldens in 1962). When protected species are found to be present on a development site, an extensive two-year study, data analysis and risk calculations must be considered prior to development.

WSB understands and adheres to the recommendations and guidance of the region 6 USFWS and the 2013 Eagle Conservation Plan Guidance when conducting site assessments for eagle use at potential wind farm locations.

Two-year data collection

This past September, we began a two-year process of raptor point count surveys to study eagle land and air usage at the wind farm site. Our environmental scientists visit Montana monthly to collect data regarding eagle activity at the site location. Field work during these evaluations includes visual eagle activity surveys, eagle nest surveys, and eagle prey abundance observation that can be used to identify the impacts of a wind farm on avian life.

We compile and record information about the weather conditions, species sitings, eagle flight paths, eagle behavior, and age class. Our scientists are not only measuring avian activity but also noting whether eagle prey, such as antelope and prairie dogs, are present. We then analyze, compile, and summarize the data for our clients. At the end of the two-year study, all data will be analyzed forecasting the potential risk to eagles from wind farm development. If risk levels are high, the client can apply for an eagle take permit through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and develop an Eagle Conservation Plan for the site.

Eagle safety is our top priority

Not all wind farms require an extensive two-year study as each potential site is different. If protected species, such as eagles, or species of concern aren’t present or observed at the site, the above approach may not be required. When risk levels for harming avian and raptor life are low, the process of wind farm development and construction can be streamlined.

This renewable energy source poses less risk to birds and wildlife than other energy sources, but it’s important to take the necessary precautions before development begins. Our environmental scientists evaluate conservation risks and make evidence-based recommendations for research, best management practices and siting locations that protect avian species with a low amount of risk. The goal for wind farm development is to help our clients develop renewable energy resources while reducing impacts to wildlife.

Environmental Scientist, Jordan Wein explains how tracking the activity of raptors can support wind farm development and minimize the risk to raptors and other birds.

Best nine of 2019

As we forge ahead into the new year, we also acknowledge and reflect on our past accomplishments.

Here are our best nine moments and industry wins of 2019.

9.Diversifying our industry through Opportunity+. Opportunity+ is part of a larger diversity and inclusion initiative centered around recruiting, welcoming, supporting, retaining and building a diverse workforce.

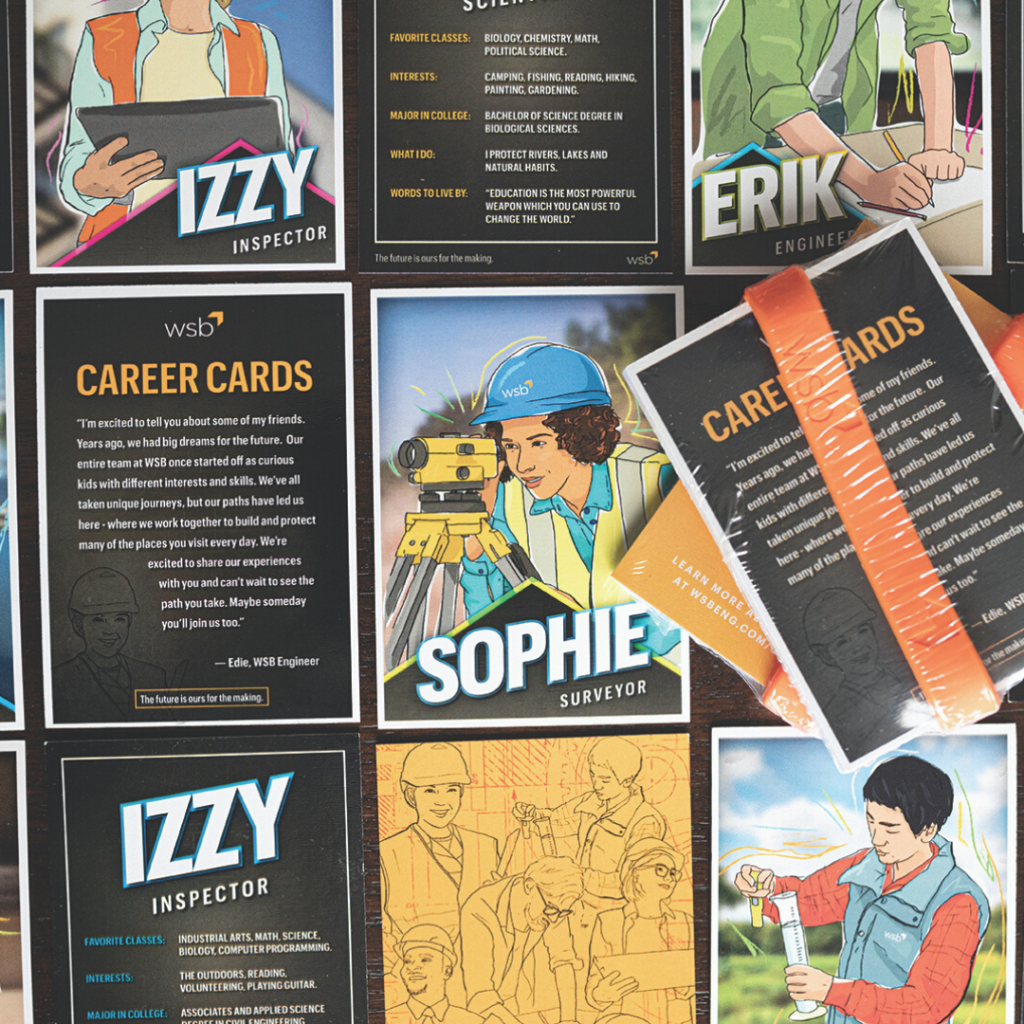

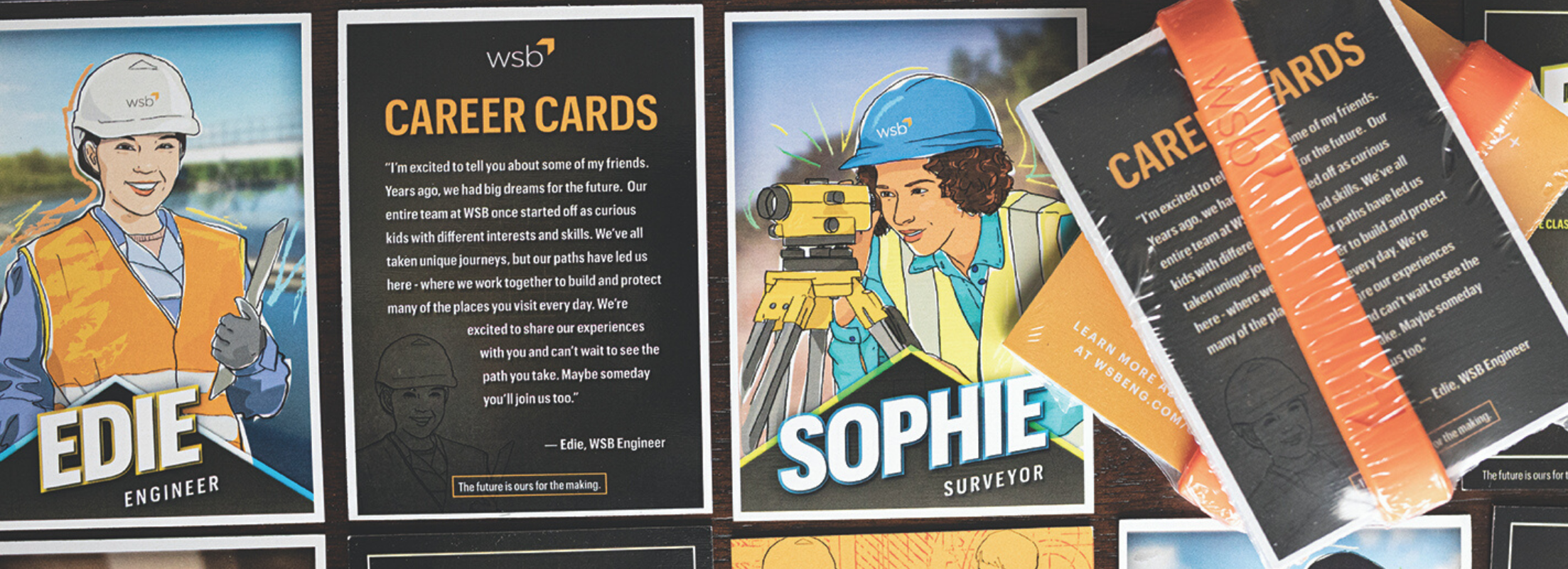

8.WSB Career Cards.

WSB recently launched a series of collectible career cards to introduce young boys and girls to the extraordinary world of engineering and STEM career possibilities.

7.WSB welcomes Chris Petree, Jody Martinson, Shelley Hanson, Klay Eckles to the team.

We made several strategic hires to help bolster our operations and better serve our clients in 2019.

6.Project award wins from APWA, CEAM, ACEC-MN.

WSB was honored to received project awards from the American Public Works Association, City Engineers Association of Minnesota and the American Council of Engineering Companies of Minnesota.

5.Celebrating 24 years.

Our President and CEO, Bret Weiss, reflected on the past 24 years at WSB.

4.Denver office expansion.

WSB opened a new Denver office to our expand region-wide services.

3.The launch of FisH2O.

Finding an eco-friendly solution to the disposal of invasive species.

2.Austin office expansion.

WSB opened a new Austin office to expand engineering, design and consulting services.

1.Industry recognition from the Star Tribune, Zweig Group and Engineering News Record.

WSB was honored to be named a Top 150 Workplace, Hot Firm and Top 500 Design Firm.

WSB receives ACEC-MN Honor Awards

Engineering Excellence Awards

On Friday, January 24, the American Council of Engineering-Minnesota (ACEC-MN) awarded WSB two Honor Awards for the Fallon Avenue Overpass and Minnesota Highway 52: Victory Drive Memorial Corridor at the 53rd Annual Excellence in Engineering Awards Banquet in Brooklyn Park.

The Engineering Excellence Awards Program recognizes engineering achievements that exhibit the highest degree of merit and ingenuity. Entries are based on originality and innovation; future value to the engineering profession; social, economic and sustainable design considerations; complexity and client expectations. Minnesota engineering firms across the state enter their most innovative projects and studies hoping to be recognized for the work they’ve done to make the state stronger.

The Fallon Avenue Overpass project is known as a bridge that connects the community. Situated along both sides of I-94, the Fallon Overpass serves as a major local connection in the city that improves transportation, economic development opportunities and public safety.

The project was conceived over two decades ago to provide a local gateway for growth and economic development for the community. Since 1994, the city of Monticello has experienced significant growth, and the Fallon Avenue Overpass provides a critical alternative crossing over I-94 to alleviate heavy traffic on Trunk Highway 25, which has approximately 40,000 vehicles per day, and CSAH 18. The over $9 million project included several project partners and required coordination of many stakeholders.

Minnesota Highway 52: Victory Drive Memorial Corridor

Along the shady stretches of Minnesota Highway 22, known locally as “Victory Drive,” 1,170 trees were planted to honor veterans from Beauford, Mankato and Mapleton. The trees represent the veterans who gave their lives in World Wars I and II.

The Minnesota Department of Transportation prioritized the total reconstruction of 11 miles of Victory Drive over two construction seasons, beginning in 2017. WSB was selected to complete preliminary and final design of the highway and the replacement of the bridge over the Cobb River, a popular canoeing route. During the project’s public outreach program, WSB’s Landscape Architectural Group was given the unique opportunity to work with the community to gather perspectives on how best to perpetuate the highway’s living veterans memorial for generations to come.

Collectible WSB Career Cards

We believe in helping to build the workforce of the future.

WSB recently launched a series of collectible career cards to introduce young boys and girls to the extraordinary world of engineering and STEM career possibilities. Each career card offers a glimpse into the lives of six characters; Edie the Engineer, Sam the Scientist, Sophie the Surveyor, Patrick the Planner, Izzy the Inspector, and Erik the Engineer. Edie and her friends have unique traits and career paths but they all share a common goal that drives them to do their best: The future is ours for the making.

“I am excited to tell you about some of my friends. Years ago, we had big dreams for the future. Our entire team at WSB once started off as curious kids with different interests and skills. We’ve all taken unique journeys, but our paths have led us here – where we work together to build and protect many of the places you visit every day. We’re excited to share our experiences with you and can’t wait to see the path you take. Maybe someday you’ll join us too.” – Edie, WSB Engineer

Solar Development and Wetland Regulation

Roxy Robertson, Environmental Scientist, WSB

Solar production in Minnesota has seen dramatic increases in the past few years and continues to grow across the state. With this rapid growth comes challenges about how to regulate the installation of panels at a local level. According to the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), Minnesota has already invested $1.9 billion on solar and additional growth is projected at 834 megawatts over the next five years. The installations of solar “farms”, vast arrays of solar panels, can be seen throughout the state and can generate up to a megawatt of electricity each. Development of these sites often requires large, vacant parcels which may also support natural habitats such as wetlands.

The development application process for these solar farms can be challenging for municipalities, especially those who act as the local government unit (LGU) for the Wetland Conservation Act (WCA). Developers must work collaboratively with LGUs to demonstrate a sequencing process that shows how their projects are avoiding, minimizing, and if necessary, replacing unavoidable wetland impacts. Under the WCA rule, the installation of posts and pilings from solar panels has traditionally not been considered a wetland impact if they do not significantly alter the wetland function and value. But, as the solar industry grows, LGUs have had questions about whether the installation of solar panels may lead to loss in wetland quality over time which would be a violation of WCA. A strong measure of wetland quality comes from the diversity of the plants within the wetland, factors like shading from panels and disturbances from construction may lead to conversion of the wetland vegetative community, and subsequently, the wetland quality. Loss of wetlands and wetland quality has overlapping effects on drinking water, lake and stream health, native wildlife, soil heath, and pollinators, all of which are important to our Minnesota ecosystems.

So why does this affect you? Many municipalities act as the LGU responsible for implementing WCA. LGUs, alongside other regulating agencies, have been struggling to make impact determinations for sites that install panels in wetlands because there is little data available that addresses the future outcomes of these natural areas. There is a growing need for baseline data about how the quality of wetland vegetation changes throughout the solar development process. If data were available, LGUs could use these as a basis for making determinations.

Having baseline data about wetland vegetative quality under solar panels is beneficial to both regulators and developers. Regulators will have a scientific basis for making wetland impact determinations within their jurisdiction and developers will see more consistency across municipalities during the permitting process. We may see that wetland quality improves under solar panels in certain circumstances through the planting of native vegetation upon completion of development. In other scenarios, wetland quality may decrease if the existing wetland was of higher quality prior to development.

WSB has started an exciting initiative to collect this baseline data at various solar sites in Minnesota. In 2019, environmental scientists at WSB surveyed wetland vegetation under existing or planned solar panels at four solar farms in varying stages of development. Additional data collection at these sites is planned for the summer of 2020. WSB is in the process of developing a Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR) grant application to expand this research in 2021 to more sites across the state and to include other metrics that may influence vegetation such as fixed-tilt or tracker panel types. Support of this research from municipalities will be important for the LCCMR application process and we encourage you to join us in the process through letters of support, in-kind hours, monetary support, or providing access to solar farms within your area. It is an exciting time in the renewable energy industry and WSB is committed to helping advance the clean energy market in a way that is sustainable to our Minnesota environment that we all cherish.

Roxy is an environmental scientist and certified wetland delineator. She has a master’s degree in ecology and is a Certified Associate Ecologist. She has completed numerous wetland delineations and has experience with wetland monitoring, ecological restoration design, environmental site assessments, field research, biological surveys, ArcGIS mapping, and GPS Trimble.

Road Reconstruction Happens Year-Round

Brandon Movall, Graduate Engineer, WSB

Road reconstruction projects affect residents of all cities, from large metropolitan areas to small rural centers. While residents are very familiar with the sight of bright orange cones and excavating machines that are shown for a few months in the summer, few know the full amount of work that goes into improving roads and public utilities the rest of the year. Here is a season by season breakdown of how a road reconstruction project comes to life:

Summer/Fall

The summer/fall season is when work on a specific project typically begins for the upcoming construction season, with the start of preliminary design. Depending on the size and complexity of the project, preliminary design can begin months or even years earlier than this time frame.

The preliminary design begins by collecting extensive information on the existing conditions of the public infrastructure in the project area. This can be done through a topographic survey of the area, taking geotechnical readings on the materials in the area, and even reviewing asset management systems or old plan sets for the project area.

Based on the information gathered, the project team (typically consisting of transportation and municipal engineers) can identify improvements needed within the project area. The team then provides a preliminary overview of proposed improvements to the project owners, private utility companies such as gas or electric that could be impacted, residents, business owners and other stakeholders in the project area. At this point, public engagement becomes critical to connect with the owners, companies, and residents to solicit feedback on the proposed improvements and gather additional information on existing conditions. This feedback can be achieved through neighborhood meetings, showcasing visualizations, and conducting community surveys.

After gathering feedback, the project team presents the proposed infrastructure improvements along with estimates on costs and schedule to the project owners, and, if the project is still supported, begins final design.

Fall/Winter

The fall/winter season is dedicated to final design of the project. The team (supported by site & landscape designers, water resource engineers and wastewater engineers) completes final design documents that specialists in infrastructure construction techniques will use build the project. These documents will complete the city’s vision for the project while ensuring it is properly engineered and safe for residents. The design includes not only the pavement that residents drive on, but also all of the public utilities in the project area, such as storm sewer, sanitary sewer and watermain.

During this time, the project will also be reviewed by permitting agencies that have jurisdiction over certain aspects of the project. These agencies, such as a county or state transportation agency, may have jurisdiction over neighboring roads. Other agencies, like a state departments of natural resources, may review the project for environmental regulations within the project area.

Once the plans and specifications are complete, the project team will share the finished design documents with the project owner. The project is then authorized to be bid for construction.

Winter/Spring

The spring season is used to bid the project and prepare for construction. After the project is authorized to be bid, a notice goes out to contractors notifying them of the project and providing them access to the plans and specifications. If a contractor is interested in constructing the project, they submit a set of documents to the project owner. These documents include insurance information, proof of bonds, and their bid of how much they believe it will cost to construct the project. At an arranged time, a contractor will be selected from those that submitted a bid.

Once a contractor has been selected, project management and construction administration begins. Preliminary construction meetings are held with the project owners, the project team, and other stakeholders, to prepare for the upcoming construction of the project.

Spring/Summer

After the preliminary and final designs are complete, construction -the most visible stage of a project – can begin during the spring/summer season. During this time, the project team monitors contractor progress on the project, and ensures that the construction is being done according to the plans and specifications that were prepared in the fall/winter. This monitoring consists of a variety of activities that include construction material testing, environmental compliance, and more.

Because the winter season is often the longest in the Midwest, the time frame for construction is extremely short. To protect the final product, some projects require contractors to wait until after winter to finish minor paving and restoration work during the following spring/summer season.

Once all of the work is complete and accepted by the project owner, the contract is finalized and closed out. Usually a maintenance period is required of the contractor, during which time they are responsible to address any workmanship or materials defects which are identified following close out.

At this point, the project is considered complete. The project owner is responsible for ongoing maintenance and repair of the infrastructure through their Public Works Department. The new seasonal cycle begins with the next project that was prioritized or identified within that community’s Capital Improvement Plan or similar planning document. Learn about how WSB can assist your community with any or all of these project cycles by visiting https://www.wsbeng.com/expertise/community/ or clicking on any of the linked services above.

Brandon is a Graduate Engineer with WSB and serves as the assistant city engineer for the City of Sunfish Lake, MN. He is experienced with reviewing developer and residential land development plans and management of cities’ Municipal State Aid Systems (MSAS) through the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT).