The Roundabout Craze

Roundabouts have been used throughout Europe and Australia for decades but have only gained popularity in the United States in the past 20 years. There are currently more than 3,500 roundabouts in the United States. Minnesota has also joined the roundabout craze, with more than 140 roundabouts built as of 2014, and upward of 20 additional roundabouts built each year.

Some jurisdictions, such as the New York State Department of Transportation and the City of Bend, Oregon, have implemented a “roundabouts first” policy. These policies require that a roundabout be analyzed and, if feasible, should be the preferred option.

To understand why roundabouts have become so popular, it is important to understand what a roundabout is and why roundabouts perform so well compared to other intersection alternatives.

What is a roundabout?

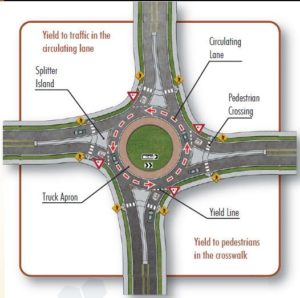

A roundabout is a type of intersection that includes a circular central island and lane(s) traveling around the central island in a counterclockwise direction. A roundabout is different from traffic circles and rotaries.

There are four main differences between rotaries/traffic circles and modern roundabouts:

Right of way

- In a roundabout, vehicles already within the circle have the right of way.

- In a rotary or traffic circle, entering vehicles have the right of way.

Size

- Roundabouts are comparatively smaller (typically 80-180 feet in diameter).

- Rotaries and traffic circles can be as big as 300-400 feet in diameter.

Changing lanes

- Changing lanes within a roundabout is not allowed. Lane integrity must be maintained through to exit.

- Changing lanes is allowed in rotaries and traffic circles (though sometimes this is difficult, as shown in the famous scene from National Lampoon’s European Vacation).

Deflection upon entry

- Deflection is crucial to appropriate roundabout design, as it promotes lower speeds and encourages yielding.

- In a rotary or traffic circle, entering traffic aims to the right of the central island, which does not promote lower speeds or yielding.

How to drive a roundabout

Roundabouts can have a variety of configurations, depending on the capacity requirements on each approach. Driving a single-lane roundabout is easier than driving a multi-lane roundabout, but the basic concept is the same. The primary concept to understand for a single-lane roundabout is this: yield to pedestrians at crosswalks and to vehicles to your left within the circulating lane.

Multi-lane roundabouts add one more step to the direction listed above: choose the appropriate lane. For example, choose the left lane if you are going left or through, and choose the right lane if you are going right or through. (Yellow line: left or through; Blue line: right or through)

Benefits of roundabouts

Compared to standard intersections, roundabouts offer significant benefits.

- Safety: This is one of the primary reasons roundabouts have become so popular. Research shows that roundabouts reduce fatal and injury accidents by as much as 76%, due to slower speeds and the existence of fewer conflict points.

- Capacity and reduced delay: Due to the continuous flow of traffic, roundabouts can handle larger volumes than signalized intersections in the same amount of time. It is a common misconception that intersections are more efficient.

- Better fuel efficiency and air quality: There is less idling by vehicles in a roundabout than in an intersection where vehicles must wait through red lights. This equates to a reduction in fuel consumption and vehicle emissions.

- Landscaping opportunities: The central island of a roundabout is a great place to provide landscaping and can serve as a gateway to a community or district.

- Safety for pedestrians: This is another common misconception about roundabouts. It is often thought that because a pedestrian crossing at a roundabout is uncontrolled, that it is not as safe as a signalized crossing. The figures below illustrate why the roundabout crossing is safer than crossings in standard intersections.

Roundabouts are being implemented in communities throughout Minnesota and continue to score well on many federal grant programs. We continue to stress the importance of educating drivers about how to properly navigate a roundabout, through ongoing communication with the public across multiple platforms.