Roxy Robertson, Environmental Scientist, WSB

Uncovering the potential issue

In the past few years, there has been a push to utilize renewable energy resources. In Minnesota and other states, there has been legislation to require some of this renewable energy to come from solar. According to the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), Minnesota ranks 13th in the nation for megawatt production, producing 1,140 MW of energy from solar. This push for solar has resulted in the development of small-scale and community solar gardens which construct panels across a variety of landscapes, including low-lying wetland areas.

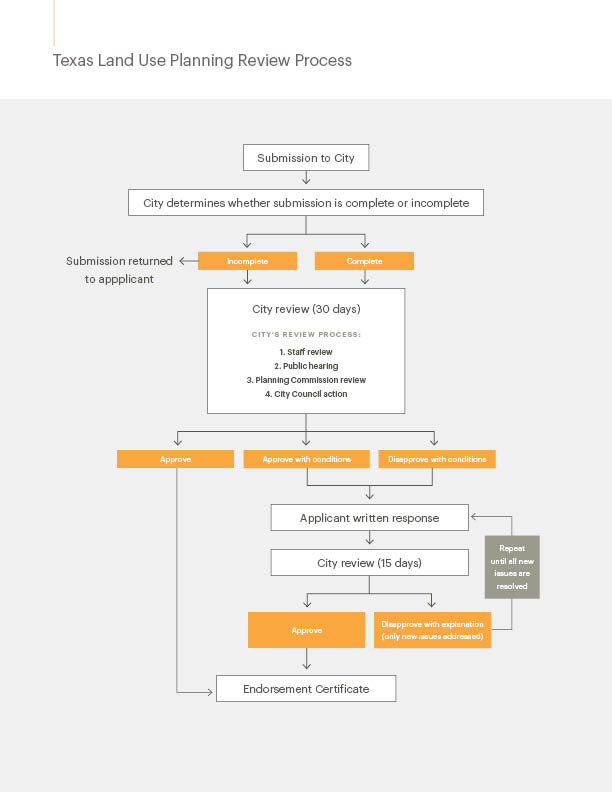

In Minnesota, there are rules and regulations for impacts to wetlands that include regulations surrounding the placement of a structure in a wetland. These rules are outlined in the Wetland Conservation Act (WCA). The WCA allows the construction of some panels in wetland areas depending on the type of impact, but regulation of these impacts is highly variable throughout the state due to lack of specific language regarding whether solar panels truly cause wetland impacts. There are opinions that suggest that the installation of solar panels within wetlands affect the quality of the wetland vegetation under the panels over time. In addition to these regulations, the Board of Water and Soil Resources (BWSR) also has standards that encourage developers of solar fields to plant vegetation that benefits pollinators.

Currently, there isn’t any research that explores the direct impact of solar panels on wetland vegetation. From small community solar gardens to large utility scale solar gardens, the energy generated can benefit communities, but what is the impact on the underlying vegetation? If solar panels are placed in a degraded wetland such as a farm field, would the installation of panels and native seed mixes improve the quality of wetland vegetation?

Where is the research?

The lack of research explaining direct impacts that solar installations have on vegetation is a challenge for scientists and engineers. Through communication with regulators and developers, we have discovered there is room for growth and study in this area, and it is a topic that needs continued exploration. This data gap has led us to develop our own vegetation studies at community solar gardens. This data is imperative if we are to continue to rely on solar energy resources. Without current guidelines that outline negative or positive effects, we are unsure of the long-term overall environmental impacts to vegetation quality under solar panels, which in turn affects the quality of natural habitat and functional benefits provided by the landscape. How do energy companies know if they are impacting the environment that surrounds solar gardens? Pursuing funding for extensive research has been challenging for those who are curious about the effects of installation of solar technology on surrounding vegetation. Even after preliminary research, many questions remain surrounding the shading of solar panels and vegetation, direct impacts, and long-term effects.

What does this mean for the future?

SEIA projects that Minnesota’s solar energy consumption will grow by 845 megawatts within the next five years. Financial support to continue this research is necessary and will allow scientists to uncover data at solar sites that does not yet exist. With this data, we can better understand the environment, impact of projects on vegetation, and develop tools to distinguish impacts. Developers looking for land will better understand the risks involved when building a solar garden on or near a wetland. As need and desire for renewable energy increases, more energy companies will implement solar. However, if we are not aware of the impacts solar gardens have, how will we know if there is an additional cost to the environment? Knowing areas to avoid allows companies to be certain of regulations, save time and money, and limit impacts to surrounding wetlands. We are continuing to complete research to better understand the impacts and benefits of solar arrays on underlying vegetation.

Roxy is an environmental scientist and certified wetland delineator. She has a master’s degree in ecology and is a Certified Associate Ecologist . She has completed numerous wetland delineations and has experience with wetland monitoring, ecological restoration design, environmental site assessments, field research, biological surveys, ArcGIS mapping, and GPS Trimble.